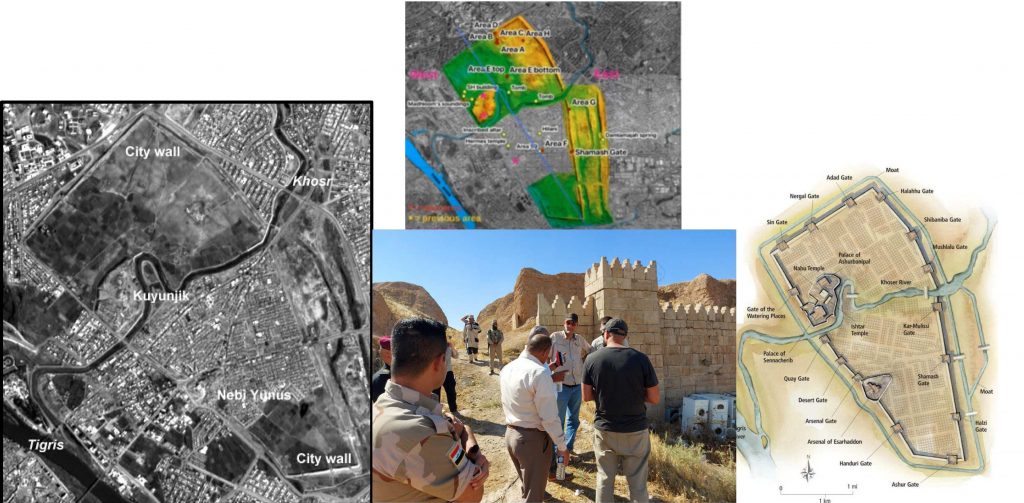

The city of Nineveh, located in Mosul, Iraq, is one of the largest archaeological sites in the world, and one of the most significant. “It’s where archaeology started, if you will,” says CRANE’s founder Prof. Timothy Harrison. “It is also still recovering from its capture by ISIS in 2014. The destruction was incredible and the people suffered immensely,” says CRANE Project Manager Stephen Batiuk. As part of the rebuilding, everyone involved needs to have up-to-date information about where archaeological remains are located and where it is or isn’t safe to build. Creating and sharing that information is part of the idea behind the Nineveh Mapping Project, a new partnership between CRANE, the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage of Iraq, and the University of Bologna. This project will pull together existing documentation from close to 200 years of excavations at the site, as well as legacy satellite imagery, and data from ongoing research to build a Geographic Information System, which aims to be eventually available to the public. “We’re going to work towards translating it to Arabic and having meetings where we share data and we talk about using the software and the programs,” says Tracy Spurrier, one of two postdoctoral fellows working on the project.

The project provides a microcosm of the importance of archaeology to new construction, since the entire archaeological site is full of areas that may be problematic for rebuilding, and many of them are poorly or incompletely documented. In consultations with our Italian partners from Bologna, the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage of Iraq and the local Municipality, the importance of this larger documentation project became obvious. The more detailed information there is about previous excavations or other changes, the easier it is to rebuild the city in an ethical and sustainable way.

Building this information database means collecting as much of the existing information as possible. Some of this information is visual; CRANE’s other postdoctoral researcher Khaled Abu-Jayyab is collecting satellite imagery from the twentieth century, which can help pinpoint the exact location of old, poorly documented excavations as well as identify other destruction or damage of archaeological remains. Spurrier, who wrote her doctoral thesis on Nineveh, is concentrating on written documentation of older excavations, dating back to the mid-19th century, trying to make “a chronological list of who was excavating and where.”

Of course, building the database is only the beginning of the work that needs to be done. Working with colleagues from Bologna and Iraq, the project also aims to incorporate local infrastructure data into the GIS, while training students, both in Iraq and Canada, to carry on the documentation work as the project moves forward. “I got a lot out of just meeting people and asking them questions, especially our fellow archaeologists who worked at Nineveh and other sites in the area for a long time,” says Spurrier. “We can do future work here, we can make friends, we can build connections.” And eventually, sections of the site will become public monuments and part of a larger archaeological park for people to visit – a reminder that archaeology is, above all, about the way human beings use the past to live, build and rebuild.

Written by Jaime Weinman.