The Tepe Gawra Lower Town Survey

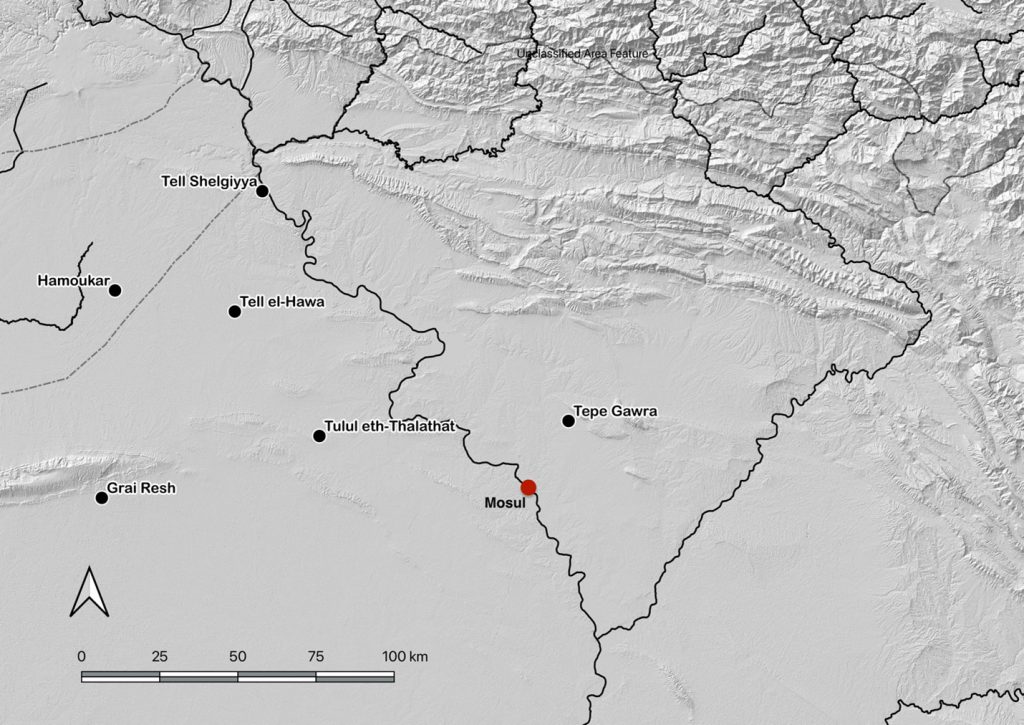

Also this past October, a second team from NMC led by Dr. Khaled Abu Jayyab (CRANE postdoctoral researcher), carried out survey work around the site of Tepe Gawra. Tepe Gawra is located roughly 20 km to the northeast of Mosul and just to the south of the town of Fadiliyah in the Ninawa Governate, Northeastern Iraq (Fig.1).

Figure 1: Location of Mosul and Tepe Gawra and other contemporary sites.

Tepe Gawra (Fig.2) has long been seen as an essential site for late prehistoric and early historic periods, not only in Iraq but for the entirety of Northern Mesopotamia. Despite its significance, work at Tepe Gawra hasn’t been carried out at the site since the 1930s. The early excavations, conducted at the site by Speiser and the University of Pennsylvania (Speiser 1927, 1935; Tobler 1950) revealed a long occupational sequence dating from the Halaf period to the mid-second millennium BC. The sequence has very few short-lived gaps in occupation and as such has become a chronological anchor for the region, especially for late prehistory (Halaf, Ubaid, and Late Chalcolithic). Analytical work carried out by Abu al-Soof (1974), and more recently Rothman (2002), has expanded our understanding of the Northern Uruk period and has been key to developing the modern Late Chalcolithic (LC1-LC5; 4600-3100 BC) chronological scheme (Rothman ed. 2001; Schwartz 2001).

Despite its small size (roughly 2-3 ha. at its base extent), Tepe Gawra has been the hallmark site for the development of complexity during the Ubaid and Late Chalcolithic periods in the ancient Near East. Excavations at the site revealed a local development of a sophisticated infrastructure manifest in the construction of temples, monumental architecture, and elaborate administrative technologies. Throughout its occupation, the site shows involvement in far-flung networks connecting it with Highland Anatolia and the Zagros mountains, with connections as far afield as Afghanistan. These connections were seen in the high concentration of objects made of exotic materials such as obsidian, lapis lazuli, carnelian, copper, gold, and silver (Rothman 2002: 8), in addition to the presence of imported utilitarian and luxury ceramics (Abu Jayyab 2019, 2022; Rothman and Blackman 2003). The households at Tepe Gawra were also shown to be involved in multiple craft activities such as woodwork, textile production, elaborate administration, stone tool manufacture, and the production of high-end ceramic wares (see Rothman 2002; Rothman and Blackman 2003).

The main mound of the site has furnished evidence of highly specialized activities (administration, exchange, and craft production) with very little evidence of agricultural implements and farming. This phenomenon is unique as this degree of specialization was only attested at larger contemporary sites that combined specialized activities with extensive farming practices (e.g. Tell Brak reaches over 100 ha during this period). This situation would have necessitated that the inhabitants of Tepe Gawra rely on an external source for food. Rothman suggested that a functional segregation between sites existed in the piedmont or the foothills during this time (Rothman 2002: 5). He saw that the site of Tepe Gawra was a ‘center’ at the top of a specialized hierarchical network. Within this network Gawra served as an administrative, religious, and craft hub (Rothman 2002: 5-6). In support of the notion of a center, Frangipane argues that the landscape played a role in limiting urbanism in the piedmont around Tepe Gawra where the terrain may have restricted the expansion of agriculture beyond its natural limit preventing the region from producing enough agricultural surpluses to support a large conglomeration (Frangipane 2009: 135).

There is no doubt as to the significance of Tepe Gawra within the region but was the site truly dependent on a large regional network for subsistence? That is, was the site serving a special function that excluded it from food production? There remains a debate as to whether or not there was a lower Chalcolithic period town around Tepe Gawra. Algaze notes (1993: 71-72) – based on personal communication with Gibson – that the mound was surrounded by a lower town. If this was true then the high mound would have simply been the acropolis of a larger town that still remains to be systematically explored. Rothman did not reject the idea of the presence of a lower town, however, he remained skeptical with the absence of empirical data (Rothman 2002: 19).

With the permission of the SBAH office in Mosul, Members of the Shamash Gate team Drs. Timothy Harrison, Khaled Abu Jayyab, and Stephen Batiuk had the chance to visit the site on October 1st 2021. The question heading to the site was whether or not the site had a lower town. Immediately upon arrival, a dense scatter of sherds was found to cover the surrounding (lower town) area of the site, and from what could be observed, most of the sherds seemed to date to the Late Chalcolithic period. This realization prompted Dr. Abu Jayyab to write a letter to the SBAH for the purpose of applying for a permit to conduct a surface survey around the main mound of Tepe Gawra.

In light of the debates and discussions surrounding Tepe Gawra, the team from NMC wanted first and foremost to systematically determine the extent of the site during each stage of occupation. With the aim of understanding if a differentiated settlement with an upper and lower town did emerge at Tepe Gawra, and if so, during which period/s did this take place. The team also wanted to explore the hypothesis proposed by Rothman regarding the site and ask whether Gawra was indeed exerting influence across a region as a ‘center’, whether it was a self-sustaining settlement exploiting its agricultural hinterland, or whether it shifted between these different organizational forms through time.

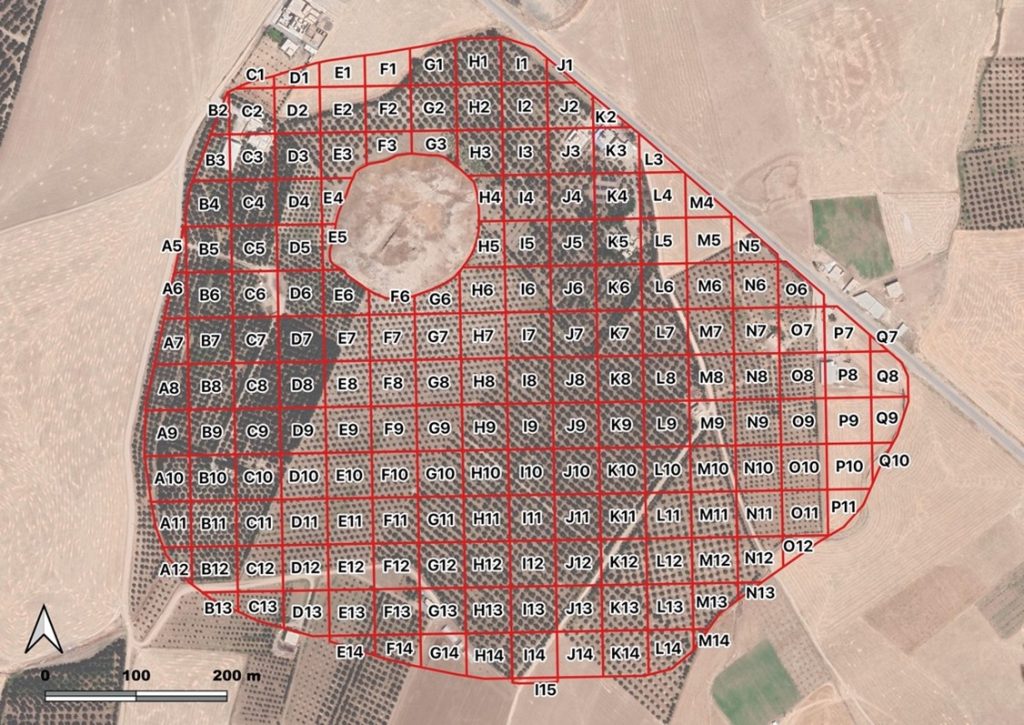

Between the 8th and the 28th of November 2022, A team from the University of Toronto (Khaled Abu Jayyab, Stephen Batiuk, Ira Schwartz, and Arno Glasser) in collaboration with local Scholars from Qadisiya University (Prof. Abbas al-Hussainy and Mr. Hossam Hadi), and members of the Mosul office of the SBAH (fig.3), carried out a systematic survey at the site (fig.4). The area was divided into 50x50m units, and artifacts from each unit were collected and recorded individually, all artifacts were taken to the mission house, cleaned, processed, drawn photographed and studied. This gave the team an understanding of the extent of the site during each period and allowed them to note the presence of any specialized activity areas in the lower town. A digital record of the site was generated through drone imagery and the generation of a digital elevation model.

Beyond the archaeological information, another important aspect of the project was to document disturbances at the site. The team was able to observe and record two main factors that have led to the destruction of features at the site, Farming activities and ISIS tunneling.

Farming activities consisted primarily of the planting of olive orchards around the site. According to local farmers, the orchard was planted roughly 30 years ago. The orchard impacted the site in a number of ways. First, clear bulldozing took place at the foot of the main mound in order to level that area and prepare it for agriculture. The majority of the dirt was pushed towards the mound forming a low embankment along the majority of the mound’s circumference. Second, the act of planting the trees, and plowing the land, in addition to the irrigation systems associated with them (including lines of watering tubes buried in the ground and running between the trees) churned up large swaths of the lower town at Tepe Gawra. Finally, the construction of a number of farmhouses, rest areas, and water collection basins with the orchard impacted the lower town significantly. All these factors make excavations of the lower town near impossible making this survey all the more important.

The most recent major damage to the site was caused by members of ISIS. The militant group dug an intricate network of tunnels within the mound (Fig.5). These tunnels may impact the integrity of the mound and might cause collapses in the near future. Besides the structural issues these tunnels caused, due to their size, the impact on the archaeological remains is equally devastating if not more.

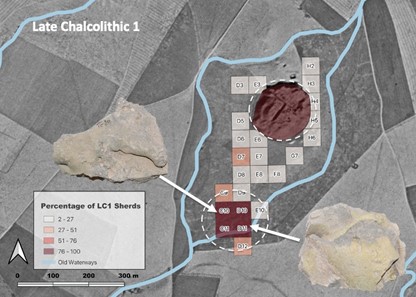

In terms of the scientific results of the mission, the team was able to document the stages of development at the site where a clear expansion from the main mound clearly began during the Late Chalcolithic 1 period (4600-4200 BC) and continued through to the Late Chalcolithic 3 period (3900-3600 BC) to at which point the site was abandoned till the Ninevite 5 period (3100-2800 BC). During the late Chalcolithic the site expands from roughly 4 ha. (Ubaid Middle Chalcolithic period, 5300-4600 BC) to 9 ha. during the LC1, and later, to 15 ha. during the LC2 and 3. Further, the team was able to isolate a number of distinct activity areas (e.g. pottery making, high-intensity farming) dating to these periods (Fig.6). All this implied that rather than being an isolated small center exclusively reliant on far-flung inter and intraregional networks, Tepe Gawra was going through similar processes of urban expansion, social differentiation, and economic specialization that were occurring at other sites in the region, albeit within its own local trajectory.

Occupation at the site reached its zenith during the latter part of the 3rd millennium or the Late Early Bronze Age (Akkadian/Ur III periods). During this period, we see the largest extent of the site reaching approximately 23 ha. The site declines during the Middle Bronze Age, and eventually shifts slightly to the north during the Late Bronze Age and the Iron Age, where the mound of Tepe Gawra itself becomes too narrow at the summit to sustain a village. The Final occupation in the environs of the site occurs during the late Sassanian/Early Islamic period where settlement shifts to the southern edges of the survey zone.

Another important aspect of the project was to foster close cooperation with local institutes and members of the community. This approach is taken as part of the steps in reforming and decolonizing excavation and survey in Iraq as outlined by Jotheri (2022). Accordingly, the project emphasized the training of local students and members of the SBAH involved. Moreover, following the season members of the project held a workshop at Qadisiya University in Diwaniya, organized by Prof. Abbas al-Hussainy, pertaining to the work at Tepe Gawra, and analytical work on ceramics, lithics, and survey methodology. The workshop was open to faculty, students, and members of the public alike (Fig.7).

The season’s work at Shamash Gate and Tepe Gawra was a resounding success despite the tight schedule. A great thanks to our team at Shamash including Dr. Tim Harrison, Dr. Tracy Spurrier and Elizabeth Gibbon, and the logistical help from Dr. Nicolo Marchetti and the East Nineveh Project team. The work at Gawra would not have been possible without the financial support provided by the ASOR Mesopotamia Fellowship, and the CRANE project (University of Toronto), In addition to the guidance, motivation, and logistical support provided by Prof. Timothy Harrison (NMC) and Prof. Abbas Al-Hussainy (Qadisiya University). Finally, the work would not have been possible without the monumental efforts of the Tepe Gawra Survey Team, Dr. Stephen Batiuk (NMC), Ira Schwartz, Arno Glasser (both U of T, Anthropology), and Hossam Hadi (Qadisiya University), whom all put in extra shifts to ensure the data was processed on time and in a scientific manner. The success of this work would not have been possible without these great teams and the SBAH of the Republic of Iraq.

Bibliography

Abu al-Soof, B. (1974). “Prehistoric Pottery from Nineveh, Gawra, and the Neighbouring Sites.” Sumer 30: 1-10.

Abu Jayyab, K. (2019). “Nomads in Late Chalcolithic Northern Mesopotamia: Mobility and Social Change in the 5th and 4th Millennium BC.” Unpublished PhD. Thesis, University of Toronto.

Abu Jayyab, K. (2022). ““North-eastern Mesopotamian Ceramic Sub-Assemblages and Their Potential for Identifying Communication Networks: The Formation of Red/Grey Ware Assemblages During Late Chalcolithic 1 and 2.” Eds P. Sconzo, M. Iamoni, L. Peyronel, and J. Baldi. in Late Chalcolithic Northern Mesopotamia in Context.105-121. Subartu XLVIII.

Algaze, G. (1993). “The Uruk World System: The Dynamics of Expansion of Early Mesopotamian Civilization.” University of Chicago Press.

Frangipane, M. (2009). “Non-urban Hierarchical Patterns of Territorial and Political Organization in in Northern Regions of Greater Mesopotamia: Tepe Gawra and Arslantepe.” Subartu XXIII: 135-148.

Jotheri, J. (2022). “Reforming (and Decolonizing) Excavations and Survey in Iraq.” ANE Today X: 12.

Rothman, M. ed. (2001). “Uruk Mesopotamia and Its Neighbors: Cross-cultural Interactions in the Era of State Formation.” School of American Research Press.

Rothman, M. (2002). “Tepe Gawra: The Evolution of a Small Prehistoric Center in Northern Iraq.” Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Press.

Rothman, M. & Blackman, J. (2003). “Late Fifth and Early Fourth Millennium Exchange Systems in Northern Mesopotamia: Chemical Characterization of Sprig and Impressed Wares.” Al-Rafidan 24: 1-21.

Schwartz, G. (2001). “Syria and the Uruk Expansion.” In Ed. Rothman. M. “Uruk Mesopotamia and Its Neighbors: Cross-cultural Interactions in the Era of State Formation.” 233-264. School of American Research Press.

Spieser, E. (1927). “Preliminary Excavations at Tepe Gawra.” The Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 9: 17-57.

Spieser, E. (1935). “Excavations at Tepe Gawra, I.” Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Tobler, A. J. (1950). “Excavations at Tepe Gawra II.” Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.