Rare drought coincided with Hittite Empire collapse

Reposted from Cornell Chronicle, 8 February, 2023.

The group’s paper, “Severe Multi-Year Drought Coincident with Hittite Collapse Around 1198-1196 BC,” published Feb. 8 in Nature.

The Hittite Empire emerged around 1650 BC in semi-arid central Anatolia, a region that includes much of modern Turkey. For the next five centuries, the Hittites were one of the major powers of the ancient world, alongside the Assyrian, Babylonian and Egyptian empires, and they remained remarkably resilient amid the various upheavals – social, political, economic and environmental – of the age. But around 1200 BC, the capital at Hattusa was abandoned, and the Hittite Empire was no more.

To find an explanation for the empire’s much-debated collapse, Sturt Manning, Distinguished Professor of Arts and Sciences in Classical Archaeology and the paper’s lead author, teamed up with Jed Sparks, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, both in the College of Arts and Sciences.

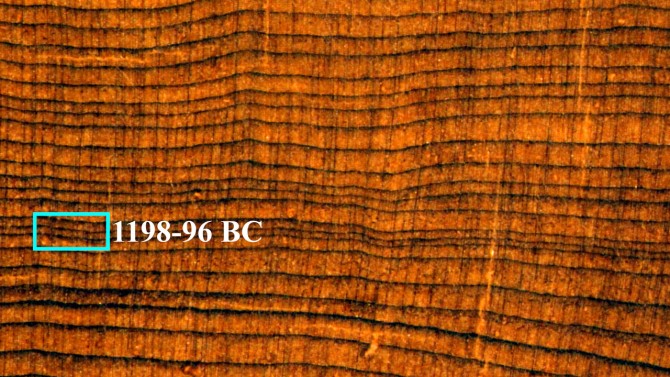

Manning and Sparks combined the capabilities of their respective labs, the Cornell Tree-Ring Laboratory and the Cornell Stable Isotope Laboratory (COIL), to scrutinize samples from the Midas Mound Tumulus at Gordion, a human-made 53-meter-tall structure located west of Ankara, Turkey. The mound contains a wooden structure believed to be a burial chamber for a relative of King Midas, possibly his father. But equally important are the juniper trees – which grow slowly and live for centuries, even a millennium – that were used to build the structure and contain a hidden paleoclimatic record of the region.

The researchers looked at the patterns of tree-ring growth, with unusually narrow rings likely indicating dry conditions, in conjunction with changes in the ratio of carbon-12 to carbon-13 recorded in the rings, which indicate the tree’s response to the availability of moisture.

“Stable isotopes are one of our strongest ways of looking into the past and asking questions about the physiological state of that plant 1,000, 2,000, 3,000 years ago,” Sparks said. “These are very, very small quantities of wood: Some of the tree-rings are only fractions of a millimeter wide. You’re basically trying to measure a neutron and a very small amount of carbon in wood. So it becomes technologically very difficult to do. Sturt and I worked for three or four years to make this work really well.”

Their analysis finds a general shift to drier conditions from the later 13th into the 12th century BC, and they peg a dramatic continuous period of severe dryness to approximately 1198–96 BC, plus or minus three years, which matches the timeline of the Hittite’s disappearance.

“We have two complementary sets of evidence,” Manning said. “The tree-ring widths indicate something really unusual is going on, and because it’s very narrow rings, that means the tree is struggling to stay alive. In a semi-arid environment, the only plausible reason that’s happening is because there’s little water, therefore it’s a drought, and this one is particularly serious for three consecutive years. Critically, the stable isotope evidence extracted from the tree-rings confirms this hypothesis, and we can establish a consistent pattern despite this all being over 3,150 years ago.”

One year of drought in a semi-arid environment would be manageable, with subsistence farmers typically having enough stored provisions to get them through the year. By the second year, a crisis would develop and “the whole system would start to break down,” said Manning, who cited the Ottoman Empire’s near collapse in the early 17th century from two consecutive years of dramatic drought.

At three consecutive years of drought, hundreds of thousands of people, including the enormous Hittite army, would face famine, even starvation. The tax base would crumble, as would the government. Survivors would be forced to migrate, an early example of the inequality of climate change.

“Probably some of what goes wrong at the end of the Bronze Age is a version of exactly what we see going wrong in the modern world, which is that groups of people are trying to move somewhere else, because they aren’t in a place that’s regarded as suitable or good,” Manning said. “They can see or hear that there are better opportunities elsewhere.”

Severe climate events may not have been the sole reason for the Hittite Empire’s collapse, the researchers noted, and not all of the ancient Near East suffered crises at the time. But this particular stretch of drought may have been a tipping point, at least for the Hittites.

“Situations where you get prolonged, really extreme events like this for two or three years are the ones that can undo even well-organized, resilient societies,” Manning said.

That finding has particular relevance today, when global populations are reckoning with catastrophic climate change and a warming planet.

“We may be approaching our own breaking point,” Manning said. “We have a range of things we can cope with, but as we are stretched too far beyond that, we’ll hit a point where our adaptative capacities are no longer matched against what we’re facing.”

Co-authors include former research associate Brita Lorentzen, ’06, Ph.D. ’15, now with the University of Georgia, and Cindy Kocik, M.A. ’14, now with the University of Wisconsin, La Crosse. The wood samples were analyzed for carbon isotope ratio by Kimberlee Sparks, a research support specialist with COIL.

The research was partially supported by the Computational Research on the Ancient Near East project, which is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and based at the University of Toronto.