We are pleased to announce the recent appointment of Dr. Kamal Badreshany to the role of Assistant Professor on a permanent basis in the Department of Archaeology, Durham University (effective from June 1, 2022).

Kamal runs the Durham Archaeomaterials Research Centre (DARC), an analytical research facility based in the Department of Archaeology that offers advanced chemical and materials analysis for academia and industry. He has overseen recent investments at Durham totalling more than £1.5 million to develop new state-of-the-art-facilities for the analysis of archaeological materials.

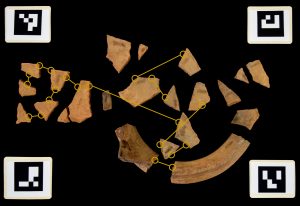

He received his PhD from the University of Chicago in 2013. His research focuses upon human adaptation to changing social, economic, and environmental conditions, especially as related to increasing settlement density and the formation of the earliest states in the Levant. He specializes in the analysis of archaeological materials using archaeometric techniques, including ceramic petrography, scanning electron microscopy, XRF, ICP and X-ray diffraction, and he has published extensively on the role of ceramics in the ancient Levant.