“Fueling the State,” a project of CRANE’s partners at Durham University in the UK, is an investigation into the properties of fuel sources that might have been used to produce pottery during the Early Bronze Age II and III. Dr. Kamal Badreshany, who spearheads the project with Prof. Graham Philip, explains that “there was a great increase in craft production” during the period, and so ceramics are among the best resources we have to understand socio-economic change. There have been relatively few studies of the fuel consumption associated with it.

The project has two basic components or sub-projects. One involves testing the different fuel sources available in the period, and the other involves reconstructing the pottery that those fuels were used to create.

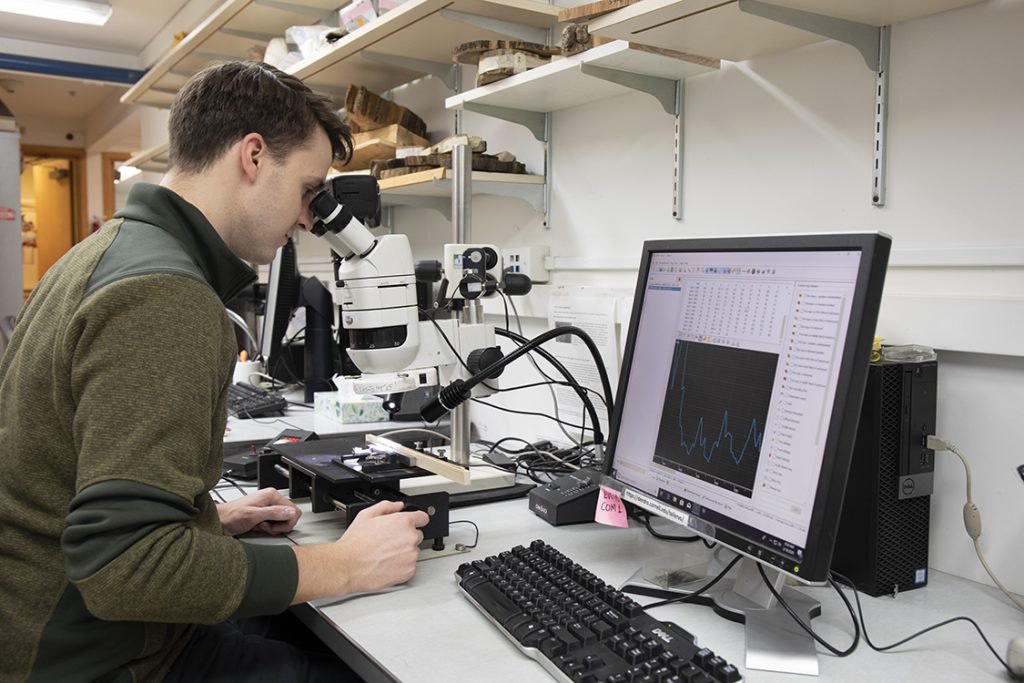

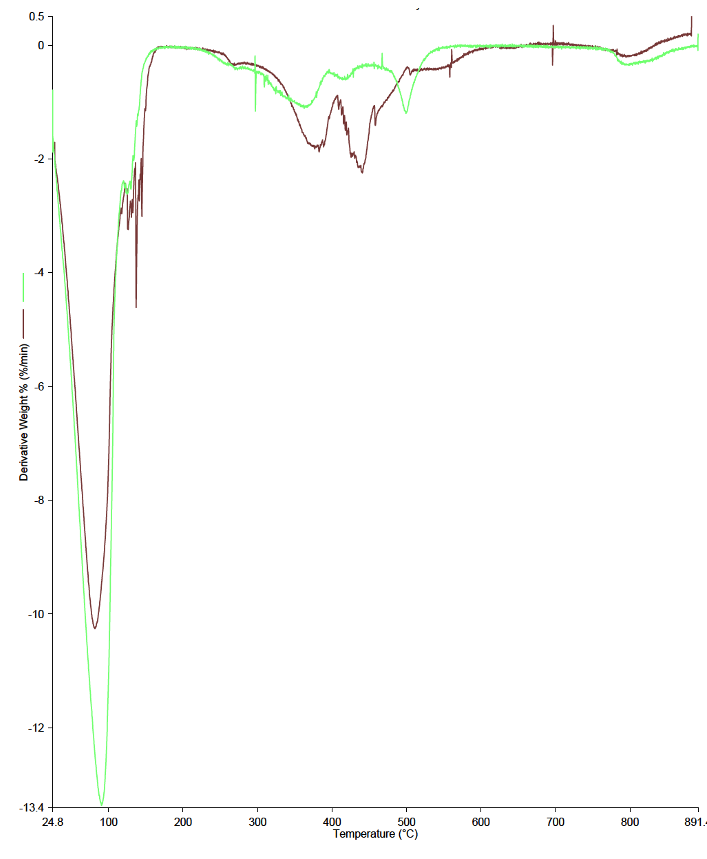

As part of the first component, Badreshany, Philip and their colleagues, who include Professor Chris Greenwell (Durham Earth Sciences) and undergraduate assistant Alice Slattery (Durham Earth Sciences), have run tests on many types of wood that could have been used as fuel in that period, as well as other fuel sources such as olive pressing waste and dung (“That’s quite an important one,” Badreshany says). To get a better understanding of how these fuels would have operated under real-world conditions, they use Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) to study how much heat it would have needed to ignite, energy release profiles, and how long it would have taken for the fuel to burn out.

Badreshany says they are finding that while wood was generally the best fuel available, waste from the production of olive oil would also have been very effective, suggesting possible links between industries: people who produced olive products might have been happy for the waste to be used as fuel, “because it is a potential environmental hazard and takes it off their hands.”

To get a better understanding of the ceramics themselves, the team has been working with experienced potters from the University of Sunderland, Rob Winter and Mary Watson. Badreshany has determined clay/temper mixes used in a particular area. The team creates “clay test cones” based on their findings, which they then fire up at different temperatures. By observing how each temperature affects the clay, its temper, and geochemistry, they will have a stronger basis for determining the source of ancient pottery and its production methods, such as the firing-temperature used by the original potters. Fuel-type and temperature profiles are key to understanding the fuel consumption and resource management needs of the time.

The team is also doing some live experiments, trying to re-create the conditions under which the original fuels were used. Badreshany says that they were recently able to “actually burn them in a fire pit and videotape that.” This real-world experiment seemed to duplicate the laboratory results, but there is one type of fuel Badreshany says they’re already pretty clear about: “Dung works, but it’s really the worst one.”

Written by Jaime Weinman.